Physical Address

304 North Cardinal St.

Dorchester Center, MA 02124

Physical Address

304 North Cardinal St.

Dorchester Center, MA 02124

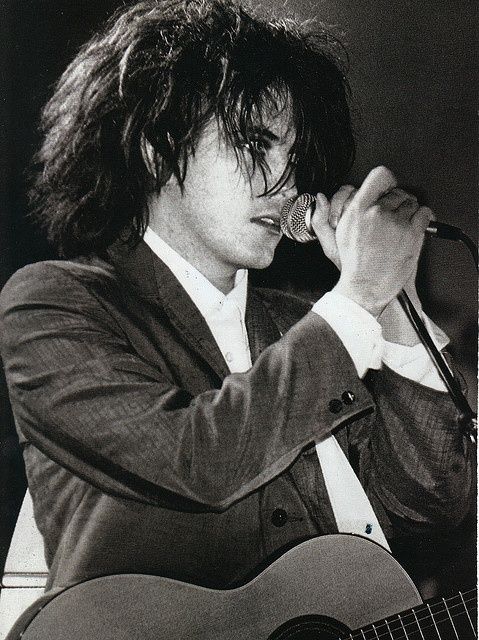

Robert Smith, the iconic leader of The Cure, is not only a pioneer of gothic rock and post-punk but also a symbol of resistance against the forces seeking to commodify art and authenticity. From his childhood in a crisis-ridden England to his fight to maintain artistic integrity amidst the increasing commercialization of music, Smith’s life and work offer a window into the complexities of modern society. Through his music, Smith has channeled the tensions of an increasingly alienating world, creating a body of work that is both a reflection of his time and an act of cultural resistance.

Robert James Smith was born on April 21, 1959, in Blackpool, England, into a working-class family. His childhood unfolded in a context of suburban normalcy but also increasing economic and social tension. The England of the 1960s and 1970s was marked by a series of economic crises that exacerbated class differences and limited opportunities for many. This material reality deeply influenced Smith’s development, fostering a sense of rootlessness and alienation that would later manifest in his music.

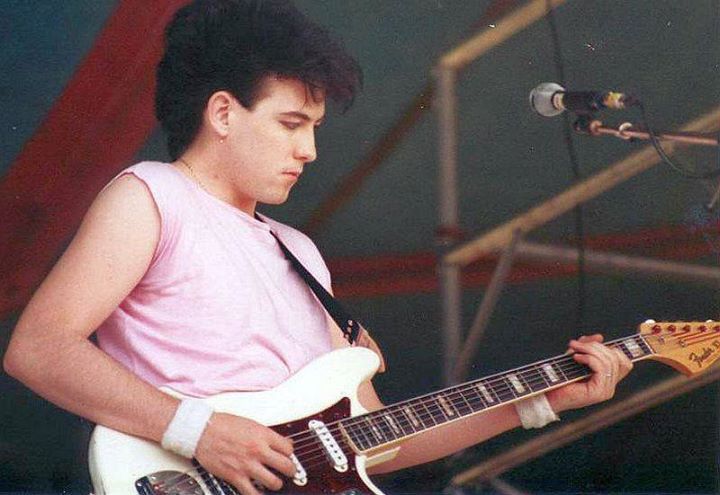

From an early age, Robert showed an inclination toward art and music, influenced by his mother, who taught him to play the piano. However, it was the guitar, a gift from his father at age 13, that captured his imagination. Inspired by The Beatles and later by artists such as Jimi Hendrix, David Bowie, and Alex Harvey, Smith began experimenting with songwriting, creating a style that combined melodic introspection with a sense of isolation and despair—reflections of the social and economic crises of his environment.

(David Bowie, 1975)

In high school, Robert formed his first band, The Crawley Goat Band, alongside his brother Richard and close friends. Although short-lived, this band gave Smith his first taste of music’s cathartic power. By the mid-1970s, Robert formed a new band called Malice, which later evolved into Easy Cure, the first incarnation of what would eventually become The Cure.

During these formative years, Smith was profoundly affected by punk rock, a movement sweeping through the UK. Punk emerged as a direct reaction to the material conditions of the time, offering a voice to a youth increasingly disconnected and frustrated by the lack of opportunities. However, while many of his contemporaries embraced punk’s nihilism, Smith went further, infusing his music with melancholic lyricism and a somber atmosphere that reflected his unique worldview.

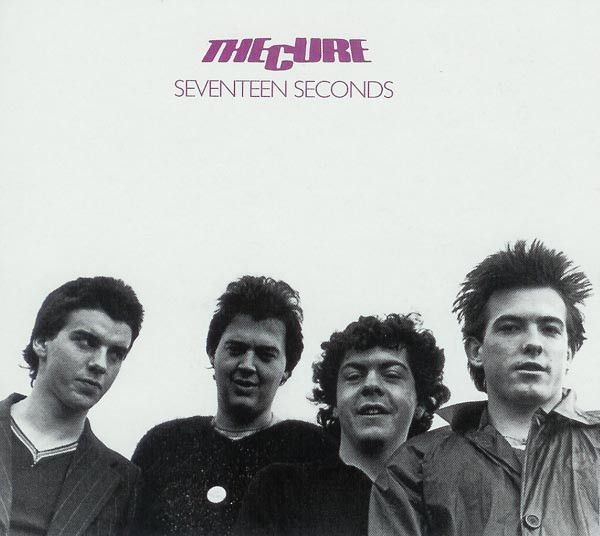

The Cure’s debut album, Three Imaginary Boys (1979), introduced a post-punk sound that was both minimalist and impactful. However, as the band gained popularity, Robert began exploring darker and more personal themes. The death of his grandmother and a failed relationship led to a period of deep introspection, culminating in the creation of Seventeen Seconds (1980), an album that marked a shift toward a more atmospheric and darker sound.

The most significant shift in Smith’s music came with the album Pornography (1982). By this time, Smith was in the throes of a personal crisis, struggling with depression and increasing substance abuse. Described by Smith as “a cry of despair,” this album is a masterpiece of hopelessness and alienation, cementing The Cure as pioneers of gothic rock. Smith’s feelings of alienation were not only personal but also a reflection of the social reality of the time: a society marked by fragmentation, disconnection, and the commercialization of all aspects of life.

Early 1980s England was undergoing an economic transformation under Margaret Thatcher’s neoliberal policies, which deepened inequality and social alienation. The increasing commodification of everyday life, including music, became a recurring theme in Smith’s work. His refusal to compromise his artistic vision under market pressures was an act of resistance against the capitalist forces that sought to reduce his art to mere consumer goods.

One of the most iconic songs from this album, “The Hanging Garden,” encapsulates this despair. The lyrics, “Creatures kissing in the rain / Shapeless in the dark again / In the hanging garden, please don’t speak,” paint a picture of desolation and hopelessness, where even moments of intimacy feel empty and grim.

In a 1989 Rolling Stone interview, Smith reflected on this dark period, saying: “I was totally alienated from everything around me. The only way I could express it was through music. I felt like I was fighting against something much bigger than myself.”

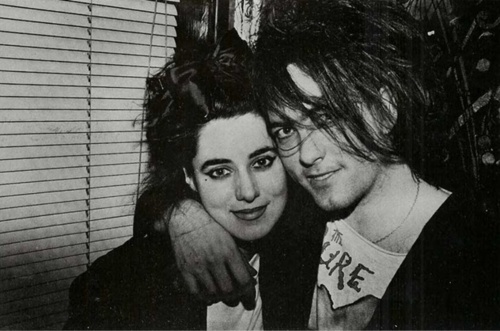

Throughout the 1980s and 1990s, Smith’s music continued to evolve, heavily influenced by changes in his personal life and the broader social context. His relationship with Mary Poole, his girlfriend since adolescence and whom he married in 1988, had a stabilizing effect on him. This emotional stability allowed Smith to explore more diverse themes in his music, ranging from the exuberant pop of The Head on the Door (1985) to the introspective and emotional Disintegration (1989), widely regarded as the pinnacle of his career.

The song “Lovesong” from Disintegration is a clear example of this emotional stability. In it, Smith sings, “However far away, I will always love you / However long I stay, I will always love you.” The simplicity and sincerity of these lyrics stand in contrast to the emotional complexities of much of his earlier work, reflecting a moment of peace and security in his personal life.

The increasing commercialization of music and the pressure to produce hits were not well received by Smith, who constantly fought to maintain the band’s artistic integrity. This internal conflict was reflected in albums such as Wish (1992), which, though more accessible, still retained the emotional complexity characteristic of his work.

In a later interview, Smith commented on the pressure of the music industry: “Music was becoming a product, something to sell. That’s always repelled me. I want our music to be something people feel deeply, not something they buy and forget.”

Smith’s music, in this sense, can be seen as a direct response to the material conditions of his environment. Albums like Pornography and Disintegration stand as testaments to the despair and existential emptiness many felt in an increasingly alienating society. These works not only reflect Smith’s individual experience but also represent a collective struggle against the forces that sought to commodify his artistic expression.

In the decades since, Smith has remained an enigmatic and creative figure. Personal events, such as his mother’s death in 2005, and the ever-changing music industry have continued to shape his work. Yet, despite the challenges, Smith has maintained his commitment to creating music that is authentic and deeply personal.

Robert Smith is more than the frontman of a band; he is a chronicler of the human experience, an artist whose music has captured the hopes, fears, and desires of generations of listeners. As The Cure continues to remain relevant, Smith’s legacy as an innovator and visionary grows. Viewed through a materialist lens, his music is not only a reflection of his time but also an act of resistance against the forces that seek to dehumanize and commodify art.

Robert Smith’s journey from an introspective child in Blackpool to a global gothic rock icon is a story of uncompromising creativity and constant evolution. His ability to transform his personal experiences and the material realities of his environment into music that resonates with millions is a testament to his artistic genius. In a world where trends come and go, Smith has demonstrated that true emotional connection in music is timeless.

Through every chord and lyric, Smith offers a resistance to being pigeonholed and commodified, maintaining authenticity in an increasingly empty world. In his work and life, Robert Smith remains a constant reminder that even in the most adverse circumstances, art can be a refuge, a form of resistance, and a voice for those who feel alienated in a world that seems not to understand them.